What Was the World’s First Video Game?

What Was the World’s First Video Game?

On a fall day in mid-October 1958, a nuclear physicist, Dr. William “Willy” Higinbotham, prepared something special for the visitors of Brookhaven National Laboratory’s annual public exhibition.

In past years, visitors—largely local students—had shown up to this event and left without really connecting to the mostly static displays showing the laboratory’s important yet complex, and difficult to understand research.

In charge of the displays for the event, Dr. Higinbotham decided he needed to create something more interactive for his visitors, something that would simultaneously entertain the guests while also showcasing the technologies used at the lab.

In the course of this work, Dr. Higinbotham created something unique, and the visitors to Brookhaven in October 1958 unwittingly became the world’s first real "gamers.”

A NUCLEAR PHYSICIST INVENTS VIDEO GAMES

It's strange that Dr. Higinbotham's place in history is inextricably intertwined with the birth of video games for several reasons.

For one Dr. Higinbotham never worked for any large toy company. He didn't found an early video game company like Atari. And, he was hardly an advocate for the video game industry during his lifetime.

Instead, in one of those happy oddities of history, Dr. Higinbotham was instead a well-respected physicist who enjoyed a long and celebrated career in government research alongside humanitarian work.

Dr. Higinbotham’s career started during World War II, when he headed the electronics group at Los Alamos National Laboratory, the lab famous for creating the first nuclear weapons.

While at Los Alamos, he was instrumental in creating the ignition system for the very first atomic bomb.

After the war, Dr. Higinbotham became deeply involved with the nuclear nonproliferation movement—a movement dedicated to decreasing the spread of nuclear weapons. He did this by helping to establish the

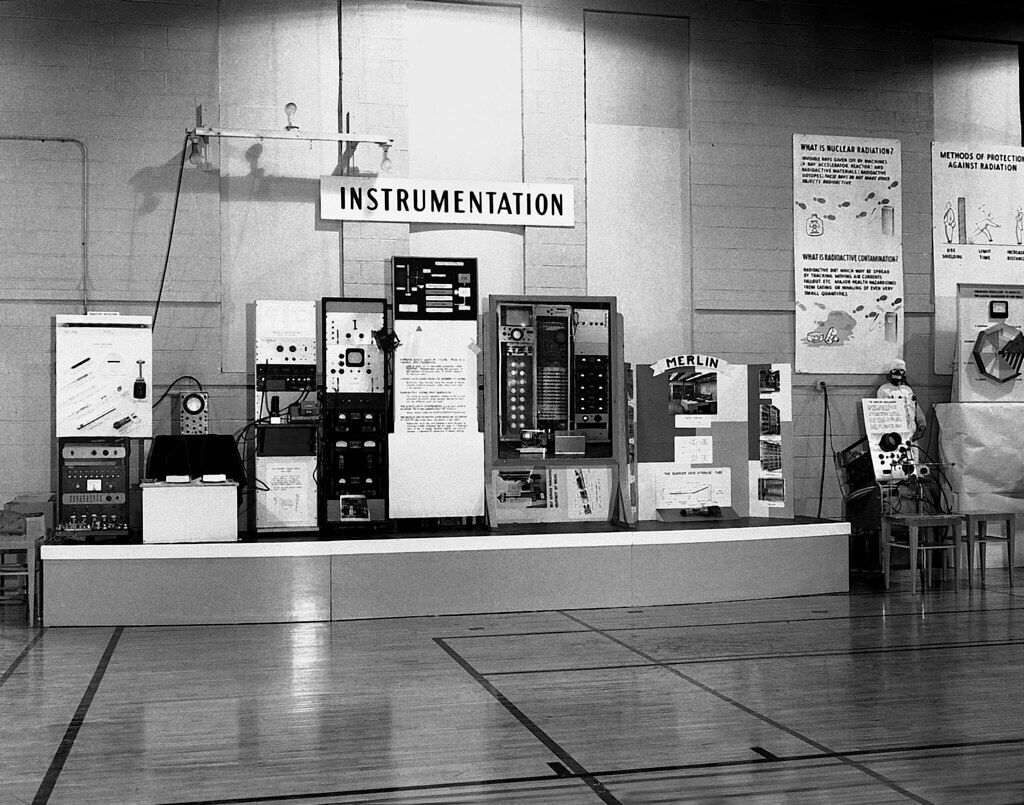

For the bulk of his career, he was a staff member at Brookhaven where he held many different positions, including working as the Head of the Instrumentation Division.

OCTOBER 18, 1958

Each year, Brookhaven National Laboratory held its annual three-day public exhibition for high school and college students as well as the general public.

The public exhibition's goal was to allow visitors to view work at the lab with the hope of spurring interest in the pursuit of science and engineering.

In the years leading up to the 1958 public exhibition, Dr. Higinbotham noticed that visitors weren't connecting with the displays created to show theiork. The exhibited displays documented interesting work, but the presentations where often too complex or boring to garner much engagement from visitors.

To fix this, Dr. Higinbotham came up with the ingenious idea to build a new display which used technology found at the lab to create an interactive presentation that guests could “play.”

Dr. Higinbotham thought it "might liven up the place to have a game that people could play, and which would convey the message that our scientific endeavors have relevance for society."

It was a brilliant leap.

To accomplish this feat, Dr. Higinbotham spent a couple hours designing a game to be played by the visitors. After several days assembling the basic parts, he turned to a lab technician named Robert Dvorak to build his vision.

What came out of this work was a simple tennis game played on an oscilloscope screen.

(An oscilloscope is a device that displays varying signal voltages, and the one he used to create his tennis game looked like the black and green radar screen every submarine has in the movies.)

The gameplay was simply by modern standards. A screen showed the side view of a tennis court with a net in the middle. The only part of the game that moved was the ball of light that was hit back and forth over the net.

Dr. Higinbotham called his game Tennis For Two.

TENNIS FOR TWO

To play Tennis For Two, two players turned a knob on a hand-held controller to change the angle of a “ball” as they hit it towards the other player's side of the court.

Players could hit the ball back at their opponent by clicking a button when the ball hit their side of the "court."

Mistimed clicks wouldn't get the ball over the net.

While playing, the game made a mechanical clicking sound, and players could see the mechanical parts clicking back and forth in the hand-held controllers as they pressed the button and spun the dial to knock the little ball of light back over the net to their opponent.

It was hardly Wii Tennis, but it was revolutionary. Furthermore, the lines of inspiration to modern video games are clear. Tennis For Two allowed players to use hand held controllers to play against one another through a game displayed on a screen.

Much more importantly to Dr. Higinbotham that October, however, was that Tennis For Two was a hit with his visitors.

Hundreds of people lined up out the door to play Tennis For Two at the exhibition, and many attendees came back for multiple games.

"It never occurred to me that I was doing anything very exciting. The long line of people I thought was not because this was so great but because all the rest of the things were so dull.”

In the end, it was so popular that the lab worried it actual detracted from the event as a whole by taking the spotlight away from the important work done there—work that has led to a total of six Nobel prizes.

HOW DID TENNIS FOR TWO WORK?

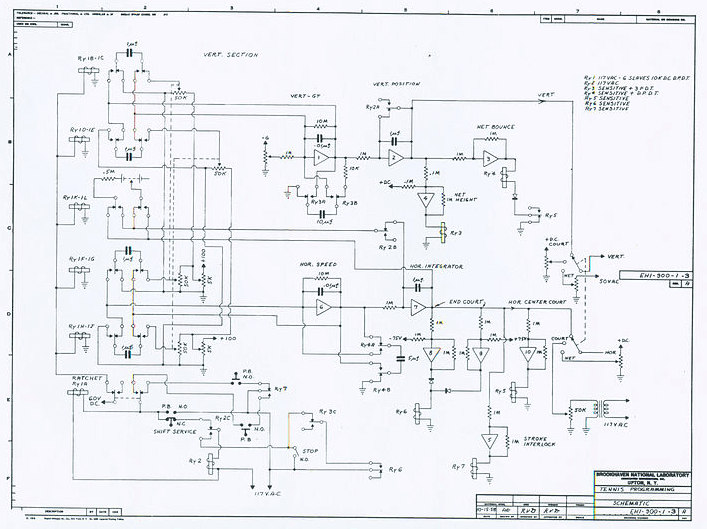

The game's basis was a Donner Model 30 analog computer, an early computer that could calculate ballistic missile trajectories. When Dr. Higinbotham learned about the computer’s capabilities, he had the idea to modify it to reproduce the varying velocity of a bouncing ball with wind resistance as opposed to the flight of a missile.

The gameplay of Tennis For Two worked by simulating the path of the ball and then reversing its path once it hit the ground. The computer could calculate if the player didn't hit it high enough to get it over the net which was how one lost the game.

Most of the game's circuitry was built with vacuums tubes and relays; the oscilloscope display, however, used transistors which were just then beginning to become standard in the electronics industry.

According to Peter Takacs who works at Brookhaven Lab and led their project to recreate Tennis For Two in 2007, “Higinbotham used the transistors to build a fast-switching circuit that would take the three outputs from the computer and display them alternately on the oscilloscope screen at a ‘blazing’ fast speed of 36 Hertz. At that display

WAS TENNIS FOR TWO REALLY THE FIRST GAME?

There is some legitimate debate over whether Tennis For Two was actually history’s first video game. Three alternative candidates are generally mentioned as earlier video games, but they all have problems that put their claims on shakier ground than Tennis For Two.

The first candidate is a device patented in 1948 called the Cathode-Ray Amusement Device. The Cathode-Ray Amusement Device used electronic signals allowing players to shoot “targets.”

Another candidate was Alan Turing's 1948 chess simulation, Turochamp.

And lastly, there was the 1952 tic-tac-toe simulation game called OXO.

These were undoubtedly necessary steps for modern video games; however, they were likely not the first video games.

A fair definition of a video game is a program that runs on a digital computer with memory, which players interact with via a screen for the purpose of entertainment.

The Cathode-Ray Amusement Device shouldn't be considered the first video game because it doesn't meet these criteria. Although it ran on an oscilloscope screen similar to Tennis For Two, it didn't use any digital computer or memory device. It also didn’t execute a program. And, it was never developed or marketed to the public, decreasing its impact on video game history.

Alan Turing's Turochamp can't be considered the first video game either as it was only a theoretical game and not built to run. Impressively, Turing wrote the code for his chess simulation before computers were powerful enough to run it.

The final candidate for the world's first video game—OXO—was a simple tic-tac-toe simulator that did run on a computer with memory. OXO was able to execute a perfect match of tic-tac-toe against players entering their moves via a rotary telephone controller.

Games like OXO have the second-best argument for being the world's first video game because they utilized a computer program and users interact with a type of interface display via a controller.

However, OXO's “display” consisted only of simple lightbulbs instead of a screen. Additionally, and importantly, OXO’s purpose was for research instead of entertainment.

Despite being essential steps vital for creating the rich world of today's video games, none of the games have a stronger argument than Tennis For Two.

Tennis For Two's Legacy

After the initial success of Tennis For Two at Brookhaven’s annual public exhibition in 1958, the team at the lab continued to improve upon and display the exhibit over the coming years.

In 1959, the team added a feature that allowed users to choose the gravity for their game, changing between Earth’s gravity and that of the Moon or Jupiter.

After several years, however, the game was ultimately discontinued and disassembled with its parts re-used for different projects around the lab.

Dr. Higinbotham never sought a patent for Tennis For Two as he never saw the vast implications his creation might have on the entertainment industry over the next half century.

He didn’t receive the proper recognition for his role in gaming history until 1982 when an article was written in Creative Computing about Tennis For Two. The writer who contributed the article played the game at Brookhaven as a child and, recognizing its place in history, wrote the article giving Dr. Higinbotham the credit he deserved.

Despite his important work in video games, it was truly his work in nuclear nonproliferation that was his passion. His son—when asked about his father’s role in video game history — requested "It is imperative that you include information on his nuclear nonproliferation work. That was what he wanted to be remembered for.”

So, to honor the service he did for the video game world as well as respect his life’s work, here is a link to the.